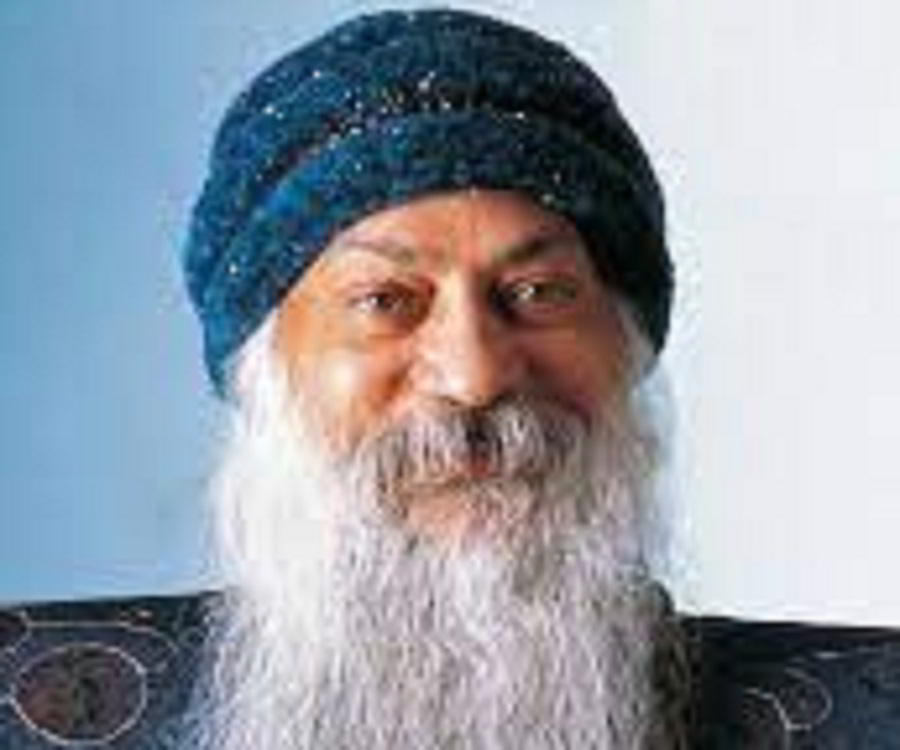

Shree Rajneesh (born Chandra Mohan Jain, 11 December 1931 – 19 January 1990), also known as Osho, Acharya Rajneesh, or simply Rajneesh, was an Indian Godman and leader of the Rajneesh movement. During his lifetime he was viewed as a controversial mystic, guru, and spiritual teacher. In the 1960s he travelled throughout India as a public speaker and was a vocal critic of socialism, Mahatma Gandhi,and Hindu religious orthodoxy. He advocated a more open attitude towards human sexuality, earning him the sobriquet "sex guru" in the Indian and later international press, although this attitude became more acceptable with time.

In 1970 Rajneesh spent time in Bombay initiating followers known as "neo-sannyasins." During this period he expanded his spiritual teachings and through his discourses gave an original insight into the writings of religious traditions, mystics, and philosophers from around the world. In 1974 Rajneesh relocated to Pune where a foundation and ashram was established to offer a variety of "transformational tools" for both Indian and international visitors. By the late 1970s, tension between the ruling Janata Party government of Morarji Desai and the movement led to a curbing of the ashram's development.

In 1981 efforts refocused on activities in the United States and Rajneesh relocated to a facility known as Rajneeshpuram in Wasco County, Oregon. Almost immediately the movement ran into conflict with county residents and the State government and a succession of legal battles concerning the ashram's construction and continued development curtailed its success. In 1985, following the investigation of serious crimes including the 1984 Rajneeshee bioterror attack, and an assassination plot to murder US Attorney Charles H. Turner, Rajneesh alleged that his personal secretary Ma Anand Sheela and her close supporters had been responsible. He was later deported from the United States in accordance with an Alford plea bargain.

After his deportation twenty-one countries denied him entry, and he ultimately returned to India, and a reinvigorated Pune ashram, where he died in 1990. His ashram is today known as the Osho International Meditation Resort. His syncretic teachings emphasise the importance of meditation, awareness, love, celebration, courage, creativity, and humor—qualities that he viewed as being suppressed by adherence to static belief systems, religious tradition, and socialisation. Rajneesh's teachings have had a notable impact on Western New Age thought,and their popularity has increased markedly since his death

Biography

Childhood and adolescence: 1931–1950

Rajneesh (a childhood nickname from Sanskrit रजनि rajani, night and ईश isha, lord) was born Chandra Mohan Jain, the eldest of eleven children of a cloth merchant, at his maternal grandparents' house in Kuchwada; a small village in the Raisen district of Madhya Pradesh state in India. His parents Babulal and Saraswati Jain, who were Taranpanthi Jains, let him live with his maternal grandparents until he was seven years old. By Rajneesh's own account, this was a major influence on his development because his grandmother gave him the utmost freedom, leaving him carefree without an imposed education or restrictions. When he was seven years old, his grandfather died, and he went to Gadarwara to live with his parents. Rajneesh was profoundly affected by his grandfather's death, and again by the death of his childhood girlfriend and cousin Shashi from typhoid when he was 15, leading to a preoccupation with death that lasted throughout much of his childhood and youth. In his school years he was a rebellious, but gifted student, and acquired a reputation as a formidable debater. Rajneesh became an anti-theist, took an interest in hypnosis and briefly associated with socialism and two Indian nationalist organisations: the Indian National Army and the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh. However, his membership in the organisations was short-lived as he could not subscribe to any external discipline, ideology or system.

University years and public speaker: 1951–1970

In 1951, aged nineteen, Rajneesh began his studies at Hitkarini College in Jabalpur.[26] Asked to leave after conflicts with an instructor, he transferred to D. N. Jain College, also in Jabalpur. Having proved himself to be disruptively argumentative, he was not required to attend college classes in D. N. Jain College except for examinations and used his free time to work for a few months as an assistant editor at a local newspaper. He began speaking in public at the annual Sarva Dharma Sammelan (Meeting of all faiths) held at Jabalpur, organised by the Taranpanthi Jain community into which he was born, and participated there from 1951 to 1968. He resisted his parents' pressure to get married. Rajneesh later said he became spiritually enlightened on 21 March 1953, when he was 21 years old, in a mystical experience while sitting under a tree in the Bhanvartal garden in Jabalpur.

Having completed his B.A. in philosophy at D. N. Jain College in 1955, he joined the University of Sagar, where in 1957 he earned his M.A. in philosophy (with distinction). He immediately secured a teaching post at Raipur Sanskrit College, but the Vice-Chancellor soon asked him to seek a transfer as he considered him a danger to his students' morality, character and religion. From 1958, he taught philosophy as a lecturer at Jabalpur University, being promoted to professor in 1960. A popular lecturer, he was acknowledged by his peers as an exceptionally intelligent man who had been able to overcome the deficiencies of his early small-town education.

In parallel to his university job, he travelled throughout India under the name Acharya Rajneesh (Acharya means teacher or professor; Rajneesh was a nickname he had acquired in childhood), giving lectures critical of socialism, Gandhi and institutional religions. He said that socialism would only socialise poverty, and he described Gandhi as a masochist reactionary who worshipped poverty. What India needed to escape its backwardness was capitalism, science, modern technology and birth control. He criticised orthodox Indian religions as dead, filled with empty ritual, oppressing their followers with fears of damnation and the promise of blessings. Such statements made him controversial, but also gained him a loyal following that included a number of wealthy merchants and businessmen. These sought individual consultations from him about their spiritual development and daily life, in return for donations—a commonplace arrangement in India—and his practice grew rapidly. From 1962, he began to lead 3- to 10-day meditation camps, and the first meditation centres (Jivan Jagruti Kendra) started to emerge around his teaching, then known as the Life Awakening Movement (Jivan JagrutiAndolan). After a controversial speaking tour in 1966, he resigned from his teaching post at the request of the university.

In a 1968 lecture series, later published under the title From Sex to Superconsciousness, he scandalised Hindu leaders by calling for freer acceptance of sex and became known as the "sex guru" in the Indian press. When in 1969 he was invited to speak at the Second World

At a public meditation event in spring 1970, Rajneesh presented his Dynamic Meditation method for the first time. He left Jabalpur for Bombay at the end of June. On 26 September 1970, he initiated his first group of disciples or neo-sannyasins. Becoming a disciple meant assuming a new name and wearing the traditional orange dress of ascetic Hindu holy men, including a mala (beaded necklace) carrying a locket with his picture. However, his sannyasins were encouraged to follow a celebratory rather than ascetic lifestyle. He himself was not to be worshipped but regarded as a catalytic agent, "a sun encouraging the flower to open".

He had by then acquired a secretary Laxmi Thakarsi Kuruwa, who as his first disciple had taken the name Ma Yoga Laxmi. Laxmi was the daughter of one of his early followers, a wealthy Jain who had been a key supporter of the National Congress Party during the struggle for Indian independence, with close ties to Gandhi, Nehru and Morarji Desai. She raised the money that enabled Rajneesh to stop his travels and settle down. In December 1970, he moved to the Woodlands Apartments in Bombay, where he gave lectures and received visitors, among them his first Western visitors. He now travelled rarely, no longer speaking at open public meetings. In 1971, he adopted the title "Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh". Shree is a polite form of address roughly equivalent to the English "Sir"; Bhagwan means "blessed one", used in Indian traditions as a term of respect for a human being in whom the divine is no longer hidden but apparent. Later, when he changed his name, he would redefine the meaning of Bhagwan.

The humid climate of Mumbai proved detrimental to Rajneesh's health: he developed diabetes, asthma and numerous allergies. In 1974, on the 21st anniversary of his experience in Jabalpur, he moved to a property in Koregaon Park, Pune, purchased with the help of Ma Yoga Mukta (Catherine Venizelos), a Greek shipping heiress. Rajneesh spoke at the Poona ashram from 1974 to 1981. The two adjoining houses and 6 acres (24,000 m2) of land became the nucleus of an ashram, and the property is still the heart of the present-day Osho International Meditation Resort. It allowed the regular audio recording and, later, video recording and printing of his discourses for worldwide distribution, enabling him to reach far larger audiences. The number of Western visitors increased sharply. The ashram soon featured an arts-and-crafts centre producing clothes, jewellery, ceramics and organic cosmetics and hosted performances of theatre, music and mime. From 1975, after the arrival of several therapists from the Human Potential Movement, the ashram began to complement meditations with a growing number of therapy groups, which became a major source of income for the ashram.

The Pune ashram was by all accounts an exciting and intense place to be, with an emotionally charged, madhouse-carnival atmosphere.in the ashram's "Buddha Hall" auditorium, commenting on religious writings or answering questions from visitors and disciples. Until 1981, lecture series held in Hindi alternated with series held in English. During the day, various meditations and therapies took place, whose intensity was ascribed to the spiritual energy of Rajneesh's "buddhafield". In evening darshans, Rajneesh conversed with individual disciples or visitors and initiated disciples ("gave sannyas"). Sannyasins came for darshan when departing or returning or when they had anything they wanted to discuss.

To decide which therapies to participate in, visitors either consulted Rajneesh or made selections according to their own preferences.Some of the early therapy groups in the ashram, such as the Encounter group, were experimental, allowing a degree of physical aggression as well as sexual encounters between participants. Conflicting reports of injuries sustained in Encounter group sessions began to appear in the press. Richard Price, at the time a prominent Human Potential Movement therapist and co-founder of the Esalen institute, found the groups encouraged participants to 'be violent' rather than 'play at being violent' (the norm in Encounter groups conducted in the United States), and criticised them for "the worst mistakes of some inexperienced Esalen group leaders". Price is alleged to have exited the Poona ashram with a broken arm following a period of eight hours locked in a room with participants armed with wooden weapons. Bernard Gunther, his Esalen colleague, fared better in Poona and wrote a book, Dying for Enlightenment, featuring photographs and lyrical descriptions of the meditations and therapy groups. Violence in the therapy groups eventually ended in January 1979, when the ashram issued a press release stating that violence "had fulfilled its function within the overall context of the ashram as an evolving spiritual commune".

Sannyasins who had "graduated" from months of meditation and therapy could apply to work in the ashram, in an environment that was consciously modelled on the community the Russian mystic Gurdjieff led in France in the 1930s. Key features incorporated from Gurdjieff were hard, unpaid work, and supervisors chosen for their abrasive personality, both designed to provoke opportunities for self-observation and transcendence. Many disciples chose to stay for years. Besides the controversy around the therapies, allegations of drug use amongst sannyasin began to mar the ashram's image. Some Western sannyasins were alleged to be financing extended stays in India through prostitution and drug-running. A few later alleged that, while Rajneesh was not directly involved, they discussed such plans and activities with him in darshan and he gave his blessing.

By the latter 1970s, the Poona ashram was too small to contain the rapid growth and Rajneesh asked that somewhere larger be found.Sannyasins from around India started looking for properties: those found included one in the province of Kutch in Gujarat and two more in India's mountainous north. The plans were never implemented as mounting tensions between the ashram and the Janata Party government of Morarji Desai resulted in an impasse. Land-use approval was denied and, more importantly, the government stopped issuing visas to foreign visitors who indicated the ashram as their main destination. In addition, Desai's government cancelled the tax-exempt status of the ashram with retrospective effect, resulting in a claim estimated at $5 million. Conflicts with various Indian religious leaders aggravated the situation—by 1980 the ashram had become so controversial that Indira Gandhi, despite a previous association between Rajneesh and the Indian Congress Party dating back to the sixties, was unwilling to intercede for it after her return to power. In May 1980, during one of Rajneesh's discourses, an attempt on his life was made by Vilas Tupe, a young Hindu fundamentalist. Tupe claims that he undertook the attack, because he believed Rajneesh to be an agent of the CIA.

By 1981, Rajneesh's ashram hosted 30,000 visitors per year. Daily discourse audiences were by then predominantly European and American. Many observers noted that Rajneesh's lecture style changed in the late seventies, becoming less focused intellectually and featuring an increasing number of ethnic or dirty jokes intended to shock or amuse his audience. On 10 April 1981, having discoursed daily for nearly 15 years, Rajneesh entered a three-and-a-half-year period of self-imposed public silence, and satsangs—silent sitting with music and readings from spiritual works such as Khalil Gibran's The Prophet or the Isha Upanishad—replaced discourses. Around the same time, Ma Anand Sheela (Sheela Silverman) replaced Ma Yoga Laxmi as Rajneesh's secretary.

The United States and the Oregon commune: 1981–1985

Further information: Rajneeshpuram

In 1981, the increased tensions around the Poona ashram, along with criticism of its activities and threatened punitive action by the Indian authorities, provided an impetus for the ashram to consider the establishment of a new commune in the United States. According to Susan J. Palmer, the move to the United States was a plan from Sheela. Gordon (1987) notes that Sheela and Rajneesh had discussed the idea of establishing a new commune in the US in late 1980, although he did not agree to travel there until May 1981.

On 1 June, he travelled to the United States on a tourist visa, ostensibly for medical purposes, and spent several months at a Rajneeshee retreat centre located at Kip's Castle in Montclair, New Jersey.[84][85] He had been diagnosed with a prolapsed disc in spring 1981 and treated by several doctors, including James Cyriax, a St. Thomas' Hospital musculoskeletal physician and expert in epidural injections flown in from London. Rajneesh's previous secretary, Laxmi, reported to Frances FitzGerald that "she had failed to find a property in India adequate to Rajneesh's needs, and thus, when the medical emergency came, the initiative had passed to Sheela". A public statement by Sheela indicated that Rajneesh was in grave danger if he remained in India, but would receive appropriate medical treatment in America if he were to require surgery. Despite the stated serious nature of the situation Rajneesh never sought outside medical treatment during his time in the United States, leading the Immigration and Naturalization Service to contend that he had a preconceived intent to remain there. Rajneesh would later plead guilty to immigration fraud, while maintaining his innocence of the charges that he made false statements on his initial visa application about his alleged intention to remain in the US when he came from India.

On 13 June 1981, Sheela's husband, John Shelfer, signed a purchase contract to buy property in Oregon for US$5.75 million, and a few days later assigned the property to the US foundation. The property was a 64,229-acre (260 km2) ranch, previously known as "The Big Muddy Ranch" and located across two Oregon counties (Wasco and Jefferson). It was renamed "Rancho Rajneesh" and Rajneesh moved there on 29 August. One Oregon professor: "The initial response in Oregon was an uneasy balance in which tolerance tended to outweigh hostility with increasing distance." The press reported, and another study found, that the development met almost immediately with intense local, state and federal opposition from the government, press and citizenry. Initial local community reactions ranged from hostility to tolerance, depending on distance from the ranch. Within months a series of legal battles ensued, principally over land use. In May 1982 the residents of Rancho Rajneesh voted to incorporate it as the city of Rajneeshpuram. 1000 Friends of Oregon immediately commenced and then prosecuted over the next six years numerous court and administrative actions to void the incorporation and cause buildings and improvement to be removed. 1000 Friends publicly called for the City to be "dismantled". A 1000 Friends Attorney stated that if 1000 Friends won, the Foundation would be “forced to remove their sewer system and tear down many of the buildings. In 1985, the Oregon Supreme Court found that the land was not suitable for farming, and therefore did not need to satisfy the complicated land use procedures and standards, but remanded for determination on other issues. In 1987, the Supreme Court finally resolved the case in favour of the City, by which time of course, the community had disbanded. During the course of the litigation, 1000 Friends ran a fundraising ad throughout Oregon headlined "Rajneeshpuram Alert. Worrying about Rajneeshpuram Won't Help." An Oregonian editorial commented on the ad, stating that 1000 Friends "ought to be ashamed of itself" for a campaign "based on fear and prejudice". Ironically, the Federal Bureau of Land Management found that the highest farm use of the land in question was the grazing of 9 cattle. At one point, the commune imported large numbers of homeless people from various US cities in a failed attempt to affect the outcome of an election, before releasing them into surrounding towns and leaving some to the State of Oregon to return them to their home cities at the state's expense

.

In March, 1982, local residents formed a group called Citizens for Constitutional Cities to oppose the Ranch development. (Hortsch, Dan 18 Mar 1982 "Fearing 'religious cities' group forms to monitor activities of commune" The Oregonian p. D28.) An initiative petition was filed which would order the governor "'to contain, control and remove' the threat of invasion by an 'alien cult'". In 1985, another state petition, supported by several Oregon legislators, was filed to invalidate the charter of the City of Rajneeshpuram. In July 1985, the venue of a civil trial was moved because studies offered by the Foundation showed bias. The judge stated that "community attitudes would not permit a fair and impartial trial". The Oregon legislature passed several bills seeking to slow or stop the development and the City of Rajneeshpuram, including HB 3080 which stopped distribution of revenue sharing funds "for any city whose legal status had been challenged. Rajneeshpuram was the only city impacted by the legislation." Oregon Gov. Vic Atiyah stated in 1982 that since their neighbours did not like them, they should leave Oregon. A representative of the community responded "all you have to do is insert the word Negro or Jew or Catholic…and it is a little easier to understand how that statement sounded." In May 1982, US Senator Mark Hatfield called the INS in Portland. An INS memo stated that the Senator was "very concerned" about this "religious cult" is "endangering the way of life for a small agricultural town…and is a threat to public safety". Such actions "often do have influence on immigration decisions". Charles Turner, the US Attorney responsible for the prosecution of the immigration case against Rajneesh, said, after Rajneesh left the US his deportation was effective because it "caused the destruction of the entire movement". In January 1989, INS Commissioner Charles Nelson acknowledged that there had been "a lot of interest" in the immigration investigation from both the Oregon Senators, the "White House and the Justice Department". And there were many "opinions, mostly like 'This is a problem, and we need to do something about it.'" Mr. Turner later acknowledged, "we were using the legal process to solve…a political problem." A noted legal expert[weasel words] on new religion reported, as to press coverage generally, that the commune was the "focus of a huge outpouring of media attention, virtually all negative in tone". The Oregonian, by far the dominant newspaper in the state, ran a full page ad in 1987 which stated that the Oregonian "contributed to the demise of the Rajneesh commune in Oregon and the banishment of Bhagwan". An Oregon State University professor of religious studies stated that the "hysteria…erodes freedom, and presents a much more serious threat than Rajneeshism, which he viewed as an emerging religion". Mr. Richardson further found that "this plethora of legal action also shows the immense power of governmental entities to deal effectively with unpopular religious groups." (id. p. 483.) He concludes his study: "Given the record…, Oregon new religions have been on trial, and usually they have lost." In 1983 the Oregon Attorney General filed a lawsuit seeking to declare the City void because of an alleged violation of the Establishment Clause of the First Amendment to the Constitution. The Court found that the City property was owned and controlled by the Foundation, and entered judgment for the State. The court disregarded the controlling US constitutional cases requiring that a violation be redressed by the "least intrusive means" necessary to correct the violation, which it had earlier cited. The City was forced to "acquiesce" in the decision, as part of a settlement of Rajneesh's immigration case.

Rajneesh greeted by sannyasins on one of his daily "drive-bys" in Rajneeshpuram. Circa 1982.

Rajneesh had withdrawn from public speaking and lecturing during the upheaval, having entered a period of "silence" that would last until November 1984, and at the commune videos of his discourses were played to audiences instead.[84] His time was spent mostly in seclusion and he communicated only with a few key disciples, including Ma Anand Sheela and his caretaker girlfriend Ma Yoga Vivek (Christine Woolf). Rajneesh lived in a trailer next to a covered swimming pool and other amenities. He did not lecture and only saw most of the residents when, daily, he would slowly drive past them as they stood by the road.[107] He gained public notoriety for the many Rolls-Royces bought for his use, eventually numbering 93 vehicles. This made him the largest single owner of the cars in the world. His followers aimed to eventually expand that collection to include 365 Rolls-Royces—for every day of the year.

In 1981, Rajneesh gave Sheela limited power of attorney and removed the limits the following year. In 1983, Sheela announced that he would henceforth speak only with her. He would later state that she kept him in ignorance. Many sannyasins expressed doubts about whether Sheela properly represented Rajneesh and many dissidents left Rajneeshpuram in protest at its autocratic leadership. Resident sannyasins without US citizenship experienced visa difficulties that some tried to overcome by marriages of convenience.Commune administrators tried to resolve Rajneesh's own difficulty in this respect by declaring him the head of a religion, "Rajneeshism":

The Oregon years saw an increased emphasis on Rajneesh's prediction that the world might be destroyed by nuclear war or other disasters sometime in the 1990s. Rajneesh had said as early as 1964 that "the third and last war is now on the way" and frequently spoke of the need to create a "new humanity" to avoid global suicide. This now became the basis for a new exclusivism, and a 1983 article in the Rajneesh Foundation Newsletter announcing that "Rajneeshism is creating a Noah's Ark of consciousness ... I say to you that except this there is no other way", increased the sense of urgency in building the Oregon commune. In March 1984, Sheela announced that Rajneesh had predicted the death of two-thirds of humanity from AIDS. Sannyasins were required to wear rubber gloves and condoms if they had sex, and to refrain from kissing, measures widely represented in the press as an extreme over-reaction since condoms were not usually recommended for AIDS prevention because AIDS was considered a homosexual disease at that stage.

During his residence in Rajneeshpuram, Rajneesh also dictated three books under the influence of nitrous oxide administered to him by his private dentist: Glimpses of a Golden Childhood, Notes of a Madman and Books I Have Loved. Sheela later stated that Rajneesh took sixty milligrams of Valium each day and was addicted to nitrous oxide. Rajneesh denied these charges when questioned about them by journalists.

1984 Bioterror attack

Further information: 1984 Rajneeshee bioterror attack

Rajneesh had coached Sheela in using media coverage to her advantage and during his period of public silence he privately stated that when Sheela spoke, she was speaking on his behalf. He had also supported her when disputes about her behaviour arose within the commune leadership, but in spring 1984, as tension amongst the inner circle peaked, a private meeting was convened with Sheela and his personal house staff. According to the testimony of Rajneesh's dentist, Swami Devageet (Charles Harvey Newman), she was admonished during a meeting, with Rajneesh declaring that his house, and not hers, was the centre of the commune.

Devageet claimed Rajneesh warned that Sheela's jealousy of anyone close to him would inevitably see them become a target.

Several months later, on 30 October 1984, he ended his period of public silence, announcing that it was time to "speak his own truths." In July 1985 he resumed daily public discourses. On 16 September 1985, a few days after Sheela and her entire management team had suddenly left the commune for Europe, Rajneesh held a press conference in which he labelled Sheela and her associates a "gang of fascists". He accused them of having committed a number of serious crimes, most of these dating back to 1984, and invited the authorities to investigate.

The alleged crimes, which he stated had been committed without his knowledge or consent, included the attempted murder of his personal physician, poisonings of public officials, wiretapping and bugging within the commune and within his own home, and a bioterror attack on the citizens of The Dalles, Oregon, using salmonella to impact the county elections. While his allegations were initially greeted with scepticism by outside observers, the subsequent investigation by the US authorities confirmed these accusations and resulted in the conviction of Sheela and several of her lieutenants. On 30 September 1985, Rajneesh denied that he was a religious teacher. His disciples burned 5,000 copies of Book of Rajneeshism, a 78-page compilation of his teachings that defined "Rajneeshism" as "a religionless religion". He said he ordered the book-burning to rid the sect of the last traces of the influence of Sheela, whose robes were also "added to the bonfire".

The salmonella attack was noted as the first confirmed instance of chemical or biological terrorism to have occurred in the United States. Rajneesh stated that because he was in silence and isolation, meeting only with Sheela, he was unaware of the crimes committed by the Rajneeshpuram leadership until Sheela and her "gang" left and sannyasins came forward to inform him. A number of commentators have stated that they believe that Sheela was being used as a convenient scapegoat. Others have pointed to the fact that although Sheela had bugged Rajneesh's living quarters and made her tapes available to the US authorities as part of her own plea bargain, no evidence has ever come to light that Rajneesh had any part in her crimes. Nevertheless, Gordon (1987) reports that Charles Turner, David Frohnmayer and other law enforcement officials, who had surveyed affidavits never released publicly and who listened to hundreds of hours of tape recordings, insinuated to him that Rajneesh as guilty of more crimes than those for which he was eventually prosecuted. Frohnmayer asserted that Rajneesh's philosophy was not "disapproving of poisoning" and that he felt he and Sheela had been "genuinely evil". Nonetheless, US Attorney Turner and Attorney General Frohnmeyer acknowledged that "they had little evidence of (Rajneesh) being involved in any of the criminal activities that unfolded at the ranch". According to court testimony by Ma Ava (Ava Avalos), a prominent disciple, Sheela played associates a tape recording of a meeting she had had with Rajneesh about the "need to kill people" in order to strengthen wavering sannyasins resolve in participating in her murderous plots: "She came back to the meeting and began to play the tape. It was a little hard to hear what he was saying. And the gist of Bhagwan's response, yes, it was going to be necessary to kill people to stay in Oregon. And that actually killing people wasn't such a bad thing. And actually Hitler was a great man, although he could not say that publicly because nobody would understand that. Hitler had great vision." Sheela initiated attempts to murder Rajneesh's caretaker and girlfriend, Ma Yoga Vivek, and his personal physician, Swami Devaraj (Dr. George Meredith), because she thought that they were a threat to Rajneesh. She had secretly recorded a conversation between Devaraj and Rajneesh "in which the doctor agreed to obtain drugs the guru wanted to ensure a peaceful death if he decided to take his own life".

On 23 October 1985, a federal grand jury indicted Rajneesh and several other disciples with conspiracy to evade immigration laws. The indictment was returned in camera, but word was leaked to Rajneesh's lawyer. Negotiations to allow Rajneesh to surrender to authorities in Portland if a warrant were issued failed. Rumours of a National Guard takeover and a planned violent arrest of Rajneesh led to tension and fears of shooting. On the strength of Sheela's tape recordings, authorities later stated the belief that there had been a plan that sannyasin women and children would have been asked to create a human shield had authorities attempted to arrest Rajneesh at the commune. On 28 October 1985, Rajneesh and a small number of sannyasins accompanying him were arrested aboard a rented Learjet at a North Carolina airstrip; according to federal authorities the group was en route to Bermuda to avoid prosecution. $58,000 in cash, 35 watches and bracelets worth $1 million were found on the aircraft. Rajneesh had by all accounts been informed neither of the impending arrest nor the reason for the journey. Officials took the full ten days legally available to transfer him from North Carolina to Portland for arraignment. After initially pleading "not guilty" to all charges and being released on bail Rajneesh, on the advice of his lawyers, entered an "Alford plea"—a type of guilty plea through which a suspect does not admit guilt, but does concede there is enough evidence to convict him—to one count of having a concealed intent to remain permanently in the US at the time of his original visa application in 1981 and one count of having conspired to have sannyasins enter into sham marriages to acquire US residency. Under the deal his lawyers made with the US Attorney's office he was given a 10-year suspended sentence, five years' probation and a $400,000 penalty in fines and prosecution costs and agreed to leave the United States, not returning for at least five years without the permission of the United States Attorney General.

As to "preconceived intent", at the time of the investigation and prosecution, federal court appellate cases and the INS regulations permitted "dual intent", a desire to stay, but a willingness to comply with the law if denied permanent residence. Further, the relevant intent is that of the employer, not the employee. Given the public nature of Rajneesh's arrival and stay, and the aggressive scrutiny by the INS, Rajneesh would appear to have had to be willing to leave the US if denied benefits. The government nonetheless prosecuted him based on preconceived intent. As to arranging a marriage, the government only claimed that Rajneesh told someone who lived in his house that they should get married in order to stay. Such encouragement appears to constitute incitement, nor a crime in the US, but not a conspiracy, which requires the formation of a plan and acts in furtherance.

Travels and return to Pune: 1985–1990

Following his exit from the US, Rajneesh returned to India, landing in Delhi on 17 November 1985. He was given a hero's welcome by his Indian disciples and denounced the United States, saying the world must "put the monster America in its place" and that "Either America must be hushed up or America will be the end of the world." He then stayed for six weeks in Himachal Pradesh. When non-Indians in his party had their visas revoked, he moved on to Kathmandu, Nepal, and then, a few weeks later, to Crete. Arrested after a few days by the KYP, he flew to Geneva, then to Stockholm and to Heathrow, but was in each case refused entry. Next Canada refused landing permission, so his plane returned to Shannon airport, Ireland, to refuel. There he was allowed to stay for two weeks, at a hotel in Limerick, on condition that he did not go out or give talks. He had been granted a Uruguayan identity card, one-year provisional residency and a possibility of permanent residency, so the party set out, stopping at Madrid, where the plane was surrounded by the Guardia Civil. He was allowed to spend one night at Dakar, then continued to Recife and Montevideo. In Uruguay, the group moved to a house at Punta del Este where Rajneesh began speaking publicly until 19 June, after which he was "invited to leave" for no official reason. A two-week visa was arranged for Jamaica but on arrival in Kingston police gave the group 12 hours to leave. Refuelling in Gander and in Madrid, Rajneesh returned to Bombay, India, on 30 July 1986.

In January 1987, Rajneesh returned to the ashram in Pune where he held evening discourses each day, except when interrupted by intermittent ill health. Publishing and therapy resumed and the ashram underwent expansion, now as a "Multiversity" where therapy was to function as a bridge to meditation. Rajneesh devised new "meditation therapy" methods such as the "Mystic Rose" and began to lead meditations in his discourses after a gap of more than ten years. His western disciples formed no large communes, mostly preferring ordinary independent living. Red/orange dress and the mala were largely abandoned, having been optional since 1985. The wearing of maroon robes—only while on ashram premises—was reintroduced in summer 1989, along with white robes worn for evening meditation and black robes for group-leaders.

In November 1987, Rajneesh expressed his belief that his deteriorating health (nausea, fatigue, pain in extremities and lack of resistance to infection) was due to poisoning by the US authorities while in prison. His doctors and former attorney, Philip J. Toelkes (Swami Prem Niren), hypothesised radiation and thallium in a deliberately irradiated mattress, since his symptoms were concentrated on the right side of his body, but presented no hard evidence. US attorney Charles H. Hunter described this as "complete fiction", while others suggested exposure to HIV or chronic diabetes and stress.

From early 1988, Rajneesh's discourses focused exclusively on Zen. In late December, he said he no longer wished to be referred to as "Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh", and in February 1989 took the name "Osho Rajneesh", shortened to "Osho" in September. He also requested that all trademarks previously branded with RAJNEESH be rebranded internationally to OSHO. His health continued to weaken. He delivered his last public discourse in April 1989, from then on simply sitting in silence with his followers. Shortly before his death, Rajneesh suggested that one or more audience members at evening meetings (now referred to as the White Robe Brotherhood) were subjecting him to some form of evil magic. A search for the perpetrators was undertaken, but none could be found.

Death

Rajneesh died on 19 January 1990, aged 58, reportedly of heart failure. His ashes were placed in his newly built bedroom in Lao Tzu House at the ashram in Pune. The epitaph reads, "OSHO // Never Born // Never Died // Only Visited this Planet Earth between // Dec 11 1931 – Jan 19 1990".

Rajneesh's teachings, delivered through his discourses, were not presented in an academic setting, but interspersed with jokes and delivered with a rhetoric that many found spellbinding. The emphasis was not static but changed over time: Rajneesh revelled in paradox and contradiction, making his work difficult to summarise. He delighted in engaging in behaviour that seemed entirely at odds with traditional images of enlightened individuals; his early lectures in particular were famous for their humor and their refusal to take anything seriously. All such behaviour, however capricious and difficult to accept, was explained as "a technique for transformation" to push people "beyond the mind".

He spoke on major spiritual traditions including Jainism, Hinduism, Hassidism, Tantrism, Taoism, Christianity, Buddhism, on a variety of Eastern and Western mystics and on sacred scriptures such as the Upanishads and the Guru Granth Sahib. The sociologist Lewis F. Carter saw his ideas as rooted in Hindu advaita, in which the human experiences of separateness, duality and temporality are held to be a kind of dance or play of cosmic consciousness in which everything is sacred, has absolute worth and is an end in itself. While his contemporary Jiddu Krishnamurti did not approve of Rajneesh, there are clear similarities between their respective teachings.

Rajneesh also drew on a wide range of Western ideas. His belief in the unity of opposites recalls Heraclitus, while his description of man as a machine, condemned to the helpless acting out of unconscious, neurotic patterns, has much in common with Freud and Gurdjieff.His vision of the "new man" transcending constraints of convention is reminiscent of Nietzsche's Beyond Good and Evil; his promotion of sexual liberation bears comparison to D. H. Lawrence; and his "dynamic" meditations owe a debt to Wilhelm Reich.

Ego and the mind

According to Rajneesh every human being is a Buddha with the capacity for enlightenment, capable of unconditional love and of responding rather than reacting to life, although the ego usually prevents this, identifying with social conditioning and creating false needs and conflicts and an illusory sense of identity that is nothing but a barrier of dreams. Otherwise man's innate being can flower in a move from the periphery to the centre.

Rajneesh views the mind first and foremost as a mechanism for survival, replicating behavioural strategies that have proven successful in the past. But the mind's appeal to the past, he said, deprives human beings of the ability to live authentically in the present, causing them to repress genuine emotions and to shut themselves off from joyful experiences that arise naturally when embracing the present moment: "The mind has no inherent capacity for joy. … It only thinks about joy." The result is that people poison themselves with all manner of neuroses, jealousies, and insecurities. He argued that psychological repression, often advocated by religious leaders, makes suppressed feelings re-emerge in another guise, and that sexual repression resulted in societies obsessed with sex. Instead of suppressing, people should trust and accept themselves unconditionally. This should not merely be understood intellectually, as the mind could only assimilate it as one more piece of information: instead meditation was needed.

Meditation

Rajneesh presented meditation not just as a practice but as a state of awareness to be maintained in every moment, a total awareness that awakens the individual from the sleep of mechanical responses conditioned by beliefs and expectations. He employed Western psychotherapy in the preparatory stages of meditation to create awareness of mental and emotional patterns.

He suggested more than a hundred meditation techniques in total. His own "active meditation" techniques are characterised by stages of physical activity leading to silence. The most famous of these remains Dynamic Meditation, which has been described as a kind of microcosm of his outlook. Performed with closed or blindfolded eyes, it comprises five stages, four of which are accompanied by music. First the meditator engages in ten minutes of rapid breathing through the nose. The second ten minutes are for catharsis: "Let whatever is happening happen. … Laugh, shout, scream, jump, shake—whatever you feel to do, do it!" Next, for ten minutes one jumps up and down with arms raised, shouting Hoo! each time one lands on the flat of the feet. At the fourth, silent stage, the meditator stops moving suddenly and totally, remaining completely motionless for fifteen minutes, witnessing everything that is happening. The last stage of the meditation consists of fifteen minutes of dancing and celebration.

Rajneesh developed other active meditation techniques, such as the Kundalini "shaking" meditation and the Nadabrahma "humming" meditation, which are less animated, although they also include physical activity of one sort or another. His later "meditative therapies" require sessions for several days, OSHO Mystic Rose comprising three hours of laughing every day for a week, three hours of weeping each day for a second week, and a third week with three hours of silent meditation. These processes of "witnessing" enable a "jump into awareness". Rajneesh believed such cathartic methods were necessary, since it was difficult for modern people to just sit and enter meditation. Once the methods had provided a glimpse of meditation people would be able to use other methods without difficulty.[citation needed]

Sannyas

Another key ingredient was his own presence as a master; "A Master shares his being with you, not his philosophy. … He never does anything to the disciple." The initiation he offered was another such device: "... if your being can communicate with me, it becomes a communion. … It is the highest form of communication possible: a transmission without words. Our beings merge. This is possible only if you become a disciple." Ultimately though, as an explicitly "self-parodying" guru, Rajneesh even deconstructed his own authority, declaring his teaching to be nothing more than a "game" or a joke. He emphasised that anything and everything could become an opportunity for meditation.

Renunciation and the "New Man"

Rajneesh saw his "neo-sannyas" as a totally new form of spiritual discipline, or one that had once existed but since been forgotten. He thought that the traditional Hindu sannyas had turned into a mere system of social renunciation and imitation. He emphasised complete inner freedom and the responsibility to oneself, not demanding superficial behavioural changes, but a deeper, inner transformation. Desires were to be accepted and surpassed rather than denied. Once this inner flowering had taken place, desires such as that for sex would be left behind.

Rajneesh said that he was "the rich man's guru" and that material poverty was not a genuine spiritual value. He had himself photographed wearing sumptuous clothing and hand-made watches and, while in Oregon, drove a different Rolls-Royce each day – his followers reportedly wanted to buy him 365 of them, one for each day of the year. Publicity shots of the Rolls-Royces were sent to the press. They may have reflected both his advocacy of wealth and his desire to provoke American sensibilities, much as he had enjoyed offending Indian sensibilities earlier.

Rajneesh aimed to create a "new man" combining the spirituality of Gautama Buddha with the zest for life embodied by Nikos Kazantzakis' Zorba the Greek: "He should be as accurate and objective as a scientist … as sensitive, as full of heart, as a poet … [and as] rooted deep down in his being as the mystic." His term the "new man" applied to men and women equally, whose roles he saw as complementary; indeed, most of his movement's leadership positions were held by women. This new man, "Zorba the Buddha", should reject neither science nor spirituality but embrace both. Rajneesh believed humanity was threatened with extinction due to over-population, impending nuclear holocaust and diseases such as AIDS, and thought many of society's ills could be remedied by scientific means. The new man would no longer be trapped in institutions such as family, marriage, political ideologies and religions. In this respect Rajneesh is similar to other counter-culture gurus, and perhaps even certain postmodern and deconstructional thinkers.

Euthanasia for crippled, blind, deaf and dumb children and genetic selection

Rajneesh spoke many times of the dangers of overpopulation, and advocated universal legalisation of contraception and abortion. He described the religious prohibitions thereof as criminal, and argued that the United Nations' declaration of the human "right to life" played into the hands of religious campaigners.

According to Rajneesh, one has no right to knowingly inflict a lifetime of suffering: life should begin only at birth, and even then, "If a child is born deaf, dumb, and we cannot do anything, and the parents are willing, the child should be put to eternal sleep" rather than "take the risk of burdening the earth with a crippled, blind child." He argued that this simply freed the soul to inhabit a healthy body instead: "Only the body goes back into its basic elements; the soul will fly into another womb. Nothing is destroyed. If you really love the child, you will not want him to live a seventy-year-long life in misery, suffering, sickness, old age. So even if a child is born, if he is not medically capable of enjoying life fully with all the senses, healthy, then it is better that he goes to eternal sleep and is born somewhere else with a better body."

He stated that the decision to have a child should be a medical matter, and that oversight of population and genetics must be kept in the realm of science, outside of politicians' control: "If genetics is in the hands of Joseph Stalin, Adolf Hitler, Benito Mussolini, what will be the fate of the world?" He believed that in the right hands, these measures could be used for good: "Once we know how to change the program, thousands of possibilities open up. We can give every man and woman the best of everything. There is no need for anyone to suffer unnecessarily. Being retarded, crippled, blind, ugly – all these will be possible to change."

Rajneesh's "Ten Commandments"

In his early days as Acharya Rajneesh, a correspondent once asked for his "Ten Commandments". In reply, Rajneesh noted that it was a difficult matter because he was against any kind of commandment, but "just for fun", set out the following:

“

Never obey anyone's command unless it is coming from within you also.

There is no God other than life itself.

Truth is within you, do not search for it elsewhere.

Love is prayer.

To become a nothingness is the door to truth. Nothingness itself is the means, the goal and attainment.

Life is now and here.

Live wakefully.

Do not swim—float.

Die each moment so that you can be new each moment.

Do not search. That which is, is. Stop and see.

He underlined numbers 3, 7, 9 and 10. The ideas expressed in these Commandments have remained constant leitmotifs in his movement.The Osho International Meditation Resort in Pune, India, attracts 200,000 visitors annually.

Legacy

While Rajneesh's teachings met with strong rejection in his home country during his lifetime, there has been a change in Indian public opinion since Rajneesh's death. In 1991, an influential Indian newspaper counted Rajneesh, along with figures such as Gautama Buddha and Mahatma Gandhi, among the ten people who had most changed India's destiny; in Rajneesh's case, by "liberating the minds of future generations from the shackles of religiosity and conformism". Rajneesh has found more acclaim in his homeland since his death than he ever did while alive.Writing in The Indian Express, columnist Tanweer Alam stated, "The late Rajneesh was a fine interpreter of social absurdities that destroyed human happiness." At a celebration in 2006, marking the 75th anniversary of Rajneesh's birth, Indian singer Wasifuddin Dagar said that Rajneesh's teachings are "more pertinent in the current milieu than they were ever before". In Nepal, there were 60 Rajneesh centres with almost 45,000 initiated disciples as of January 2008. Rajneesh's entire works have been placed in the Library of India's National Parliament in New Delhi. Prominent figures such as Indian Prime Minister Manmohan Singh and the Indian Sikh writer Khushwant Singh have expressed their admiration for Osho. The Bollywood actor and Rajneeshdisciple Vinod Khanna, who had worked as Rajneesh's gardener in Rajneeshpuram, served as India's Minister of State for External Affairs from 2003 to 2004. Over 650 books are credited to Rajneesh, expressing his views on all facets of human existence. Virtually all of them are renderings of his taped discourses. His books are available in more than 60 different languages and have entered best-seller lists in countries such as Italy and South Korea.

Rajneesh continues to be a known and published worldwide in the area of meditation and his work also includes social and political commentary. Transcriptions of his discourses are published in more than 60 languages and are available from more than 200 different publishing houses. Internationally, after almost two decades of controversy and a decade of accommodation, Rajneesh's movement has established itself in the market of new religions. His followers have redefined his contributions, reframing central elements of his teaching so as to make them appear less controversial to outsiders. Societies in North America and Western Europe have met them half-way, becoming more accommodating to spiritual topics such as yoga and meditation. The Osho International Foundation (OIF) runs stress management seminars for corporate clients such as IBM and BMW, with a reported (2000) revenue between $15 and $45 million annually in the US

Rajneesh's ashram in Pune has become the Osho International Meditation Resort, one of India's main tourist attractions. Describing itself as the Esalen of the East, it teaches a variety of spiritual techniques from a broad range of traditions and promotes itself as a spiritual oasis, a "sacred space" for discovering one's self and uniting the desires of body and mind in a beautiful resort environment. According to press reports, it attracts some 200,000 people from all over the world each year; prominent visitors have included politicians, media personalities and the Dalai Lama. Before anyone is allowed to enter the resort, an HIV test is required, and those who are discovered to have the disease are not allowed in. In 2011, a national seminar on Rajneesh's teachings was inaugurated at the Department of Philosophy of the Mankunwarbai College for Women in Jabalpur. Funded by the Bhopal office of the University Grants Commission, the seminar focused on Rajneesh's "Zorba the Buddha" teaching, seeking to reconcile spirituality with the materialist and objective approach.

Reception

Rajneesh is generally considered one of the most controversial spiritual leaders to have emerged from India in the twentieth century. His message of sexual, emotional, spiritual, and institutional liberation, as well as the pleasure he took in causing offence, ensured that his life was surrounded by controversy. Rajneesh became known as the "sex guru" in India, and as the "Rolls-Royce guru" in the United States. He attacked traditional concepts of nationalism, openly expressed contempt for politicians, and poked fun at the leading figures of various religions, who in turn found his arrogance unbearable. His teachings on sex, marriage, family, and relationships contradicted traditional values and aroused a great deal of anger and opposition around the world. His movement was widely feared and loathed as a cult. Rajneesh was seen to live "in ostentation and offensive opulence", while his followers, most of whom had severed ties with outside friends and family and donated all or most of their money and possessions to the commune, might be at a mere "subsistence level".

Appraisal by scholars of religion

Academic assessments of Rajneesh's work have been mixed and often directly contradictory. Uday Mehta saw errors in his interpretation of Zen and Mahayana Buddhism, speaking of "gross contradictions and inconsistencies in his teachings" that "exploit" the "ignorance and gullibility" of his listeners. The sociologist Bob Mullan wrote in 1983 of "a borrowing of truths, half-truths and occasional misrepresentations from the great traditions"... often bland, inaccurate, spurious and extremely contradictory". Hugh B. Urban also said Rajneesh's teaching was neither original nor especially profound, and concluded that most of its content had been borrowed from various Eastern and Western philosophies. George Chryssides, on the other hand, found such descriptions of Rajneesh's teaching as a "potpourri" of various religious teachings unfortunate because Rajneesh was "no amateur philosopher". Drawing attention to Rajneesh's academic background he stated that; "Whether or not one accepts his teachings, he was no charlatan when it came to expounding the ideas of others." He described Rajneesh as primarily a Buddhist teacher, promoting an independent form of "Beat Zen" and viewed the unsystematic, contradictory and outrageous aspects of Rajneesh's teachings as seeking to induce a change in people, not as philosophy lectures aimed at intellectual understanding of the subject.

Similarly with respect to Rajneesh's embracing of western counter-culture and the human potential movement, though Mullan acknowledged that Rajneesh's range and imagination were second to none, and that many of his statements were quite insightful and moving, perhaps even profound at times, he perceived "a potpourri of counter-culturalist and post-counter-culturalist ideas" focusing on love and freedom, the need to live for the moment, the importance of self, the feeling of "being okay", the mysteriousness of life, the fun ethic, the individual's responsibility for their own destiny, and the need to drop the ego, along with fear and guilt. To Mehta Rajneesh's appeal to his Western disciples was based on his social experiments, which established a philosophical connection between the Eastern guru tradition and the Western growth movement. He saw this as a marketing strategy to meet the desires of his audience, Urban, too, viewed Rajneesh as negating a dichotomy between spiritual and material desires, reflecting the preoccupation with the body and sexuality characteristic of late capitalist consumer culture in tune with the socio-economic conditions of his time.

Peter B. Clarke confirmed that most participators felt they had made progress in self-actualization as defined by American psychologist Abraham Maslow and the human potential movement. He stated that the style of therapy Rajneesh devised, with its liberal attitude towards sexuality as a sacred part of life, had proved influential among other therapy practitioners and new age groups. Yet Clarke believes that the main motivation of seekers joining the movement was "neither therapy nor sex, but the prospect of becoming enlightened, in the classical Buddhist sense".

In 2005, Urban observed that Rajneesh had undergone a "remarkable apotheosis" after his return to India, and especially in the years since his death, going on to describe him as a powerful illustration of what F. Max Müller, over a century ago, called "that world-wide circle through which, like an electric current, Oriental thought could run to the West and Western thought return to the East". Clarke also noted that Rajneesh has come to be "seen as an important teacher within India itself" who is "increasingly recognised as a major spiritual teacher of the twentieth century, at the forefront of the current 'world-accepting' trend of spirituality based on self-development".

Appraisal as charismatic leader

A number of commentators have remarked upon Rajneesh's charisma. Comparing Rajneesh with Gurdjieff, Anthony Storr wrote that Rajneesh was "personally extremely impressive", noting that "many of those who visited him for the first time felt that their most intimate feelings were instantly understood, that they were accepted and unequivocally welcomed rather than judged. [Osho] seemed to radiate energy and to awaken hidden possibilities in those who came into contact with him". Many sannyasins have stated that hearing Rajneesh speak, they "fell in love with him." Susan J. Palmer noted that even critics attested to the power of his presence. James S. Gordon, a psychiatrist and researcher, recalls inexplicably finding himself laughing like a child, hugging strangers and having tears of gratitude in his eyes after a glance by Rajneesh from within his passing Rolls-Royce. Frances FitzGerald concluded upon listening to Rajneesh in person that he was a brilliant lecturer, and expressed surprise at his talent as a comedian, which had not been apparent from reading his books, as well as the hypnotic quality of his talks, which had a profound effect on his audience. Hugh Milne (Swami Shivamurti), an ex-devotee who between 1973 and 1982 worked closely with Rajneesh as leader of the Poona Ashram Guard and as his personal bodyguard,noted that their first meeting left him with a sense that far more than words had passed between them: "There is no invasion of privacy, no alarm, but it is as if his soul is slowly slipping inside mine, and in a split second transferring vital information." Milne also observed another facet of Rajneesh's charismatic ability in stating that he was "a brilliant manipulator of the unquestioning disciple".

Hugh B. Urban noted that Rajneesh appeared to fit with Max Weber's classical image of the charismatic figure, being held to possess "an extraordinary supernatural power or 'grace', which was essentially irrational and affective" Rajneesh corresponded to Weber's pure charismatic type in rejecting all rational laws and institutions and claiming to subvert all hierarchical authority, though Urban notes that the promise of absolute freedom inherent in this resulted in bureaucratic organisation and institutional control within larger communes.

Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh

Some scholars have suggested that Rajneesh, like other charismatic leaders, may have had a narcissistic personality.In his paper The Narcissistic Guru: A Profile of Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh, Ronald O. Clarke, Emeritus Professor of Religious Studies at Oregon State University, argued that Rajneesh exhibited all the typical features of narcissistic personality disorder, such as a grandiose sense of self-importance and uniqueness; a preoccupation with fantasies of unlimited success; a need for constant attention and admiration; a set of characteristic responses to threats to self-esteem; disturbances in interpersonal relationships; a preoccupation with personal grooming combined with frequent resorting to prevarication or outright lying; and a lack of empathy. Drawing on Rajneesh's reminiscences of his childhood in his book Glimpses of a Golden Childhood, he suggested that Rajneesh suffer

ed from a fundamental lack of parental discipline, due to his growing up in the care of overindulgent grandparents. Rajneesh's self-avowed Buddha status, he concluded, was part of a delusional system associated with his narcissistic personality disorder; a condition of ego-inflation rather than egolessness.

In 1970 Rajneesh spent time in Bombay initiating followers known as "neo-sannyasins." During this period he expanded his spiritual teachings and through his discourses gave an original insight into the writings of religious traditions, mystics, and philosophers from around the world. In 1974 Rajneesh relocated to Pune where a foundation and ashram was established to offer a variety of "transformational tools" for both Indian and international visitors. By the late 1970s, tension between the ruling Janata Party government of Morarji Desai and the movement led to a curbing of the ashram's development.

In 1981 efforts refocused on activities in the United States and Rajneesh relocated to a facility known as Rajneeshpuram in Wasco County, Oregon. Almost immediately the movement ran into conflict with county residents and the State government and a succession of legal battles concerning the ashram's construction and continued development curtailed its success. In 1985, following the investigation of serious crimes including the 1984 Rajneeshee bioterror attack, and an assassination plot to murder US Attorney Charles H. Turner, Rajneesh alleged that his personal secretary Ma Anand Sheela and her close supporters had been responsible. He was later deported from the United States in accordance with an Alford plea bargain.

After his deportation twenty-one countries denied him entry, and he ultimately returned to India, and a reinvigorated Pune ashram, where he died in 1990. His ashram is today known as the Osho International Meditation Resort. His syncretic teachings emphasise the importance of meditation, awareness, love, celebration, courage, creativity, and humor—qualities that he viewed as being suppressed by adherence to static belief systems, religious tradition, and socialisation. Rajneesh's teachings have had a notable impact on Western New Age thought,and their popularity has increased markedly since his death

Biography

Childhood and adolescence: 1931–1950

Rajneesh (a childhood nickname from Sanskrit रजनि rajani, night and ईश isha, lord) was born Chandra Mohan Jain, the eldest of eleven children of a cloth merchant, at his maternal grandparents' house in Kuchwada; a small village in the Raisen district of Madhya Pradesh state in India. His parents Babulal and Saraswati Jain, who were Taranpanthi Jains, let him live with his maternal grandparents until he was seven years old. By Rajneesh's own account, this was a major influence on his development because his grandmother gave him the utmost freedom, leaving him carefree without an imposed education or restrictions. When he was seven years old, his grandfather died, and he went to Gadarwara to live with his parents. Rajneesh was profoundly affected by his grandfather's death, and again by the death of his childhood girlfriend and cousin Shashi from typhoid when he was 15, leading to a preoccupation with death that lasted throughout much of his childhood and youth. In his school years he was a rebellious, but gifted student, and acquired a reputation as a formidable debater. Rajneesh became an anti-theist, took an interest in hypnosis and briefly associated with socialism and two Indian nationalist organisations: the Indian National Army and the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh. However, his membership in the organisations was short-lived as he could not subscribe to any external discipline, ideology or system.

University years and public speaker: 1951–1970

In 1951, aged nineteen, Rajneesh began his studies at Hitkarini College in Jabalpur.[26] Asked to leave after conflicts with an instructor, he transferred to D. N. Jain College, also in Jabalpur. Having proved himself to be disruptively argumentative, he was not required to attend college classes in D. N. Jain College except for examinations and used his free time to work for a few months as an assistant editor at a local newspaper. He began speaking in public at the annual Sarva Dharma Sammelan (Meeting of all faiths) held at Jabalpur, organised by the Taranpanthi Jain community into which he was born, and participated there from 1951 to 1968. He resisted his parents' pressure to get married. Rajneesh later said he became spiritually enlightened on 21 March 1953, when he was 21 years old, in a mystical experience while sitting under a tree in the Bhanvartal garden in Jabalpur.

Having completed his B.A. in philosophy at D. N. Jain College in 1955, he joined the University of Sagar, where in 1957 he earned his M.A. in philosophy (with distinction). He immediately secured a teaching post at Raipur Sanskrit College, but the Vice-Chancellor soon asked him to seek a transfer as he considered him a danger to his students' morality, character and religion. From 1958, he taught philosophy as a lecturer at Jabalpur University, being promoted to professor in 1960. A popular lecturer, he was acknowledged by his peers as an exceptionally intelligent man who had been able to overcome the deficiencies of his early small-town education.

In parallel to his university job, he travelled throughout India under the name Acharya Rajneesh (Acharya means teacher or professor; Rajneesh was a nickname he had acquired in childhood), giving lectures critical of socialism, Gandhi and institutional religions. He said that socialism would only socialise poverty, and he described Gandhi as a masochist reactionary who worshipped poverty. What India needed to escape its backwardness was capitalism, science, modern technology and birth control. He criticised orthodox Indian religions as dead, filled with empty ritual, oppressing their followers with fears of damnation and the promise of blessings. Such statements made him controversial, but also gained him a loyal following that included a number of wealthy merchants and businessmen. These sought individual consultations from him about their spiritual development and daily life, in return for donations—a commonplace arrangement in India—and his practice grew rapidly. From 1962, he began to lead 3- to 10-day meditation camps, and the first meditation centres (Jivan Jagruti Kendra) started to emerge around his teaching, then known as the Life Awakening Movement (Jivan JagrutiAndolan). After a controversial speaking tour in 1966, he resigned from his teaching post at the request of the university.

In a 1968 lecture series, later published under the title From Sex to Superconsciousness, he scandalised Hindu leaders by calling for freer acceptance of sex and became known as the "sex guru" in the Indian press. When in 1969 he was invited to speak at the Second World

At a public meditation event in spring 1970, Rajneesh presented his Dynamic Meditation method for the first time. He left Jabalpur for Bombay at the end of June. On 26 September 1970, he initiated his first group of disciples or neo-sannyasins. Becoming a disciple meant assuming a new name and wearing the traditional orange dress of ascetic Hindu holy men, including a mala (beaded necklace) carrying a locket with his picture. However, his sannyasins were encouraged to follow a celebratory rather than ascetic lifestyle. He himself was not to be worshipped but regarded as a catalytic agent, "a sun encouraging the flower to open".

He had by then acquired a secretary Laxmi Thakarsi Kuruwa, who as his first disciple had taken the name Ma Yoga Laxmi. Laxmi was the daughter of one of his early followers, a wealthy Jain who had been a key supporter of the National Congress Party during the struggle for Indian independence, with close ties to Gandhi, Nehru and Morarji Desai. She raised the money that enabled Rajneesh to stop his travels and settle down. In December 1970, he moved to the Woodlands Apartments in Bombay, where he gave lectures and received visitors, among them his first Western visitors. He now travelled rarely, no longer speaking at open public meetings. In 1971, he adopted the title "Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh". Shree is a polite form of address roughly equivalent to the English "Sir"; Bhagwan means "blessed one", used in Indian traditions as a term of respect for a human being in whom the divine is no longer hidden but apparent. Later, when he changed his name, he would redefine the meaning of Bhagwan.

The humid climate of Mumbai proved detrimental to Rajneesh's health: he developed diabetes, asthma and numerous allergies. In 1974, on the 21st anniversary of his experience in Jabalpur, he moved to a property in Koregaon Park, Pune, purchased with the help of Ma Yoga Mukta (Catherine Venizelos), a Greek shipping heiress. Rajneesh spoke at the Poona ashram from 1974 to 1981. The two adjoining houses and 6 acres (24,000 m2) of land became the nucleus of an ashram, and the property is still the heart of the present-day Osho International Meditation Resort. It allowed the regular audio recording and, later, video recording and printing of his discourses for worldwide distribution, enabling him to reach far larger audiences. The number of Western visitors increased sharply. The ashram soon featured an arts-and-crafts centre producing clothes, jewellery, ceramics and organic cosmetics and hosted performances of theatre, music and mime. From 1975, after the arrival of several therapists from the Human Potential Movement, the ashram began to complement meditations with a growing number of therapy groups, which became a major source of income for the ashram.

The Pune ashram was by all accounts an exciting and intense place to be, with an emotionally charged, madhouse-carnival atmosphere.in the ashram's "Buddha Hall" auditorium, commenting on religious writings or answering questions from visitors and disciples. Until 1981, lecture series held in Hindi alternated with series held in English. During the day, various meditations and therapies took place, whose intensity was ascribed to the spiritual energy of Rajneesh's "buddhafield". In evening darshans, Rajneesh conversed with individual disciples or visitors and initiated disciples ("gave sannyas"). Sannyasins came for darshan when departing or returning or when they had anything they wanted to discuss.

To decide which therapies to participate in, visitors either consulted Rajneesh or made selections according to their own preferences.Some of the early therapy groups in the ashram, such as the Encounter group, were experimental, allowing a degree of physical aggression as well as sexual encounters between participants. Conflicting reports of injuries sustained in Encounter group sessions began to appear in the press. Richard Price, at the time a prominent Human Potential Movement therapist and co-founder of the Esalen institute, found the groups encouraged participants to 'be violent' rather than 'play at being violent' (the norm in Encounter groups conducted in the United States), and criticised them for "the worst mistakes of some inexperienced Esalen group leaders". Price is alleged to have exited the Poona ashram with a broken arm following a period of eight hours locked in a room with participants armed with wooden weapons. Bernard Gunther, his Esalen colleague, fared better in Poona and wrote a book, Dying for Enlightenment, featuring photographs and lyrical descriptions of the meditations and therapy groups. Violence in the therapy groups eventually ended in January 1979, when the ashram issued a press release stating that violence "had fulfilled its function within the overall context of the ashram as an evolving spiritual commune".

Sannyasins who had "graduated" from months of meditation and therapy could apply to work in the ashram, in an environment that was consciously modelled on the community the Russian mystic Gurdjieff led in France in the 1930s. Key features incorporated from Gurdjieff were hard, unpaid work, and supervisors chosen for their abrasive personality, both designed to provoke opportunities for self-observation and transcendence. Many disciples chose to stay for years. Besides the controversy around the therapies, allegations of drug use amongst sannyasin began to mar the ashram's image. Some Western sannyasins were alleged to be financing extended stays in India through prostitution and drug-running. A few later alleged that, while Rajneesh was not directly involved, they discussed such plans and activities with him in darshan and he gave his blessing.

By the latter 1970s, the Poona ashram was too small to contain the rapid growth and Rajneesh asked that somewhere larger be found.Sannyasins from around India started looking for properties: those found included one in the province of Kutch in Gujarat and two more in India's mountainous north. The plans were never implemented as mounting tensions between the ashram and the Janata Party government of Morarji Desai resulted in an impasse. Land-use approval was denied and, more importantly, the government stopped issuing visas to foreign visitors who indicated the ashram as their main destination. In addition, Desai's government cancelled the tax-exempt status of the ashram with retrospective effect, resulting in a claim estimated at $5 million. Conflicts with various Indian religious leaders aggravated the situation—by 1980 the ashram had become so controversial that Indira Gandhi, despite a previous association between Rajneesh and the Indian Congress Party dating back to the sixties, was unwilling to intercede for it after her return to power. In May 1980, during one of Rajneesh's discourses, an attempt on his life was made by Vilas Tupe, a young Hindu fundamentalist. Tupe claims that he undertook the attack, because he believed Rajneesh to be an agent of the CIA.

By 1981, Rajneesh's ashram hosted 30,000 visitors per year. Daily discourse audiences were by then predominantly European and American. Many observers noted that Rajneesh's lecture style changed in the late seventies, becoming less focused intellectually and featuring an increasing number of ethnic or dirty jokes intended to shock or amuse his audience. On 10 April 1981, having discoursed daily for nearly 15 years, Rajneesh entered a three-and-a-half-year period of self-imposed public silence, and satsangs—silent sitting with music and readings from spiritual works such as Khalil Gibran's The Prophet or the Isha Upanishad—replaced discourses. Around the same time, Ma Anand Sheela (Sheela Silverman) replaced Ma Yoga Laxmi as Rajneesh's secretary.

The United States and the Oregon commune: 1981–1985

Further information: Rajneeshpuram

In 1981, the increased tensions around the Poona ashram, along with criticism of its activities and threatened punitive action by the Indian authorities, provided an impetus for the ashram to consider the establishment of a new commune in the United States. According to Susan J. Palmer, the move to the United States was a plan from Sheela. Gordon (1987) notes that Sheela and Rajneesh had discussed the idea of establishing a new commune in the US in late 1980, although he did not agree to travel there until May 1981.

On 1 June, he travelled to the United States on a tourist visa, ostensibly for medical purposes, and spent several months at a Rajneeshee retreat centre located at Kip's Castle in Montclair, New Jersey.[84][85] He had been diagnosed with a prolapsed disc in spring 1981 and treated by several doctors, including James Cyriax, a St. Thomas' Hospital musculoskeletal physician and expert in epidural injections flown in from London. Rajneesh's previous secretary, Laxmi, reported to Frances FitzGerald that "she had failed to find a property in India adequate to Rajneesh's needs, and thus, when the medical emergency came, the initiative had passed to Sheela". A public statement by Sheela indicated that Rajneesh was in grave danger if he remained in India, but would receive appropriate medical treatment in America if he were to require surgery. Despite the stated serious nature of the situation Rajneesh never sought outside medical treatment during his time in the United States, leading the Immigration and Naturalization Service to contend that he had a preconceived intent to remain there. Rajneesh would later plead guilty to immigration fraud, while maintaining his innocence of the charges that he made false statements on his initial visa application about his alleged intention to remain in the US when he came from India.