George Washington (February 22, 1732 [O.S. February 11, 1731][b][c] – December 14, 1799) was the first President of the United States (1789–97), the Commander-in-Chief of the Continental Army during the American Revolutionary War, and one of theFounding Fathers of the United States. He presided over the convention that drafted the current United States Constitution and during his lifetime was called the "father of his country".[2]

Widely admired for his strong leadership qualities, Washington was unanimously elected president in the first two national elections. He oversaw the creation of a strong, well-financed national government that maintained neutrality in the French Revolutionary Wars, suppressed the Whiskey Rebellion, and won acceptance among Americans of all types.[3] Washington's incumbency established many precedents, still in use today, such as the cabinet system, the inaugural address, and the title Mr. President.[4][5] His retirement from office after two terms established a tradition that lasted until 1940, when Franklin Delano Roosevelt won an unprecedented third term. The 22nd Amendment (1951) now limits the president to two elected terms. Born into the provincial gentry of Colonial Virginia, his family were wealthy planters who owned tobacco plantations and slaves which he inherited. He owned hundreds of slaves throughout his lifetime, but his views on slavery evolved to support abolition.[6] In his youth he became a senior British officer in the colonial militia during the first stages of the French and Indian War. In 1775 the Second Continental Congress commissioned Washington as commander-in-chief of the Continental Army in the American Revolution. In that command, Washington forced the British out of Boston in 1776, but was defeated and nearly captured later that year when he lost New York City. After crossing the Delaware River in the middle of winter, he defeated the British in two battles (Trenton and Princeton), retook New Jersey and restored momentum to the Patriot cause.

| General of the Armies George Washington | |

|---|---|

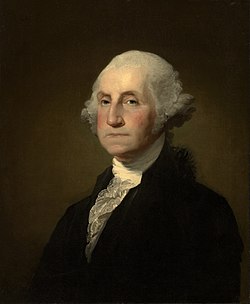

George Washington by Gilbert Stuart, 1797

| |

| 1st President of the United States | |

| In office April 30, 1789[a] – March 4, 1797 | |

| Vice President | John Adams |

| Preceded by | Inaugural holder |

| Succeeded by | John Adams |

| Senior Officer of the Army | |

| In office July 13, 1798 – December 14, 1799 | |

| Appointed by | John Adams |

| Preceded by | James Wilkinson |

| Succeeded by | Alexander Hamilton |

| Commander-in-Chief of the Continental Army | |

| In office June 15, 1775 – December 23, 1783 | |

| Appointed by | Continental Congress |

| Preceded by | Inaugural holder |

| Succeeded by | Henry Knox (Senior Officer of the Army) |

| Delegate to the Second Continental Congress from Virginia | |

| In office May 10, 1775 – June 15, 1775 | |

| Preceded by | Inaugural holder |

| Succeeded by | Thomas Jefferson |

| Delegate to the First Continental Congress from Virginia | |

| In office September 5, 1774 – October 26, 1774 | |

| Preceded by | Inaugural holder |

| Succeeded by | Position abolished |

| Personal details | |

| Born | February 22, 1732 Westmoreland County,Virginia, British America |

| Died | December 14, 1799 (aged 67) Mount Vernon, Virginia, U.S. |

| Resting place | Washington Family Tomb Mount Vernon, Virginia |

| Political party | None |

| Spouse(s) | Martha Dandridge (m. 1759) |

| Religion | Christian, Episcopal Church[1] |

| Awards | Congressional Gold Medal Thanks of Congress |

| Signature | |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | |

| Service/branch | |

| Years of service | 1752–58 (British Militia) 1775–83 (Continental Army) 1798–99 (U.S. Army) |

| Rank | |

| Commands | Virginia Colony's regiment Continental Army United States Army |

| Battles/wars | |

His strategy enabled Continental forces to capture two major British armies at Saratoga in 1777 and Yorktown in 1781. Historians laud Washington for the selection and supervision of his generals, preservation and command of the army, coordination with the Congress, state governors and their militia, and attention to supplies, logistics, and training. In battle, however, Washington was repeatedly outmaneuvered by British generals with larger armies. After victory had been finalized in 1783, Washington resigned as commander-in-chief rather than seize power, proving his opposition to dictatorship and his commitment to American republicanism.[7] Washington presided over the Constitutional Convention in 1787, which devised a new form of federal governmentfor the United States. Following unanimous election as president in 1789, he worked to unify rival factions in the fledgling nation. He supported Alexander Hamilton's programs to satisfy all debts, federal and state, established a permanent seat of government, implemented an effective tax system, and created a national bank.[8] In avoiding war with Great Britain, he guaranteed a decade of peace and profitable trade by securing the Jay Treaty in 1795, despite intense opposition from the Jeffersonians. Although he remained nonpartisan, never joining the Federalist Party, he largely supported its policies. Washington's Farewell Address was an influential primer on civic virtue, warning against partisanship, sectionalism, and involvement in foreign wars. He retired from the presidency in 1797, returning to his home and plantation at Mount Vernon.

While in power, his use of national authority pursued many ends, especially the preservation of liberty, reduction of regional tensions, and promotion of a spirit of American nationalism.[9] Upon his death, Washington was eulogized as "first in war, first in peace, and first in the hearts of his countrymen" by Henry Lee.[10] Revered in life and in death, scholarly and public polling consistently rankshim among the top three presidents in American history; he has been depicted and remembered in monuments, currency, and other dedications through the present day.